GUIDES: Choosing a Distillery Type

What type of craft distillery?

The first step in starting your own craft distillery is to decide what type of distillery you want to own. There are two basic types of distilleries and then a multitude of hybrids in between them. The most common type of distillery is the distillery bar. In the states where it is allowed, a distillery bar is primarily focused on making spirits for its own retail sales. These sales are typically by the glass in the form of cocktails or straight spirits. While the volume of spirits sold at a distillery bar are smaller than other models, they typically have much higher margins and lower equipment costs. Distillery bars also are able to turn a profit sooner—sometimes even in their first year. One important consideration to make that can decide whether a distillery bar is right for you is to research the regulations that exist in the state you’ll be operating your distillery. We strongly suggest looking up your state regulations at the start of your business planning to ensure you will be allowed to do what you want to.

On the other end of the spectrum is the distribution distillery. In a distribution distillery, the sale of spirits are most commonly to distributors and at wholesale prices. In this model, the sales volume is typically much higher than a distillery bar, but the margins are the lowest of any distillery model. What most people think of when they think of a distillery is the distribution distillery—the model where you become the next Jack Daniels. It takes time to succeed as a distribution facility, both from the time it takes to get brand recognition and the time it takes to create and mature your spirits. Generally, a distribution facility will need more startup capital to purchase larger equipment and a bigger facility in order to produce higher volumes of spirits and more operating cash to survive the “workup” period when you’re gaining recognition and getting your spirits ready for distribution.

In between these two models is where more distilleries fall. While the initial plan may be for purely retail sales, it’s very typical for a distillery bar to also have a barrel aging room in order to start working on storing away their dream bourbon in quantities that can go to distribution once they’re properly matured. One of the more common hybrid models that we’ve seen in the industry is the distillery bar that is hoping to can their specialty cocktails and distribute them. The canned cocktail or RTD spirits market is something that appeals to a lot of distilleries for a few reasons. First, you are able to use spirits that aren’t matured as long, so the time to volume distribution is shorter. And, since you aren’t using as much of the spirit, the taxes per unit volume are lower. Lastly, smaller equipment can make a larger volume for distribution.

Knowing what your goals are for your distillery is another very important consideration when figuring out the right distillery model. Without measurable goals, it is easy to miss-size equipment or pay for the trendy downtown location that doesn’t benefit from the thousands of people that walk past it every day. 10-20% of the distilleries that we build typically choose the distribution model and a similar percentage choose to just be a bar. While that leaves roughly 60-80% to choose a hybrid of the two models, the vast majority are distillery bars that either have additional space to expand their equipment and grow into distribution in their current facility or are considering the canned cocktail market for their early distribution plans.

Selecting the true middle-of-the-road model of, say, a semi out-of-the-way facility with a bar and low enough rent to also do distribution, is rarely a good idea and something we strongly discourage. Trying to do both will likely end up diluting your revenue streams and the attention and recognition you’re trying to create. And while your spirits may be good, the bar and the market plan both tend to be executed poorly. Instead, think carefully about your distillery and where you want it to go to select the right model.

Selecting your Spirits

Once you’ve chosen how you want to get your spirits to market, it’s time to decide what you want to sell. There are two major concerns to think about here. First, you need to look at actual data to get a sense for demand. Then, you need to do some general surveying of your community to see what people are drinking. If you are thinking about opening a gin bar in a town of 100 people where you and your partner are the only gin drinkers, you probably won’t be successful.

Volume & Sales Data By Spirit Type

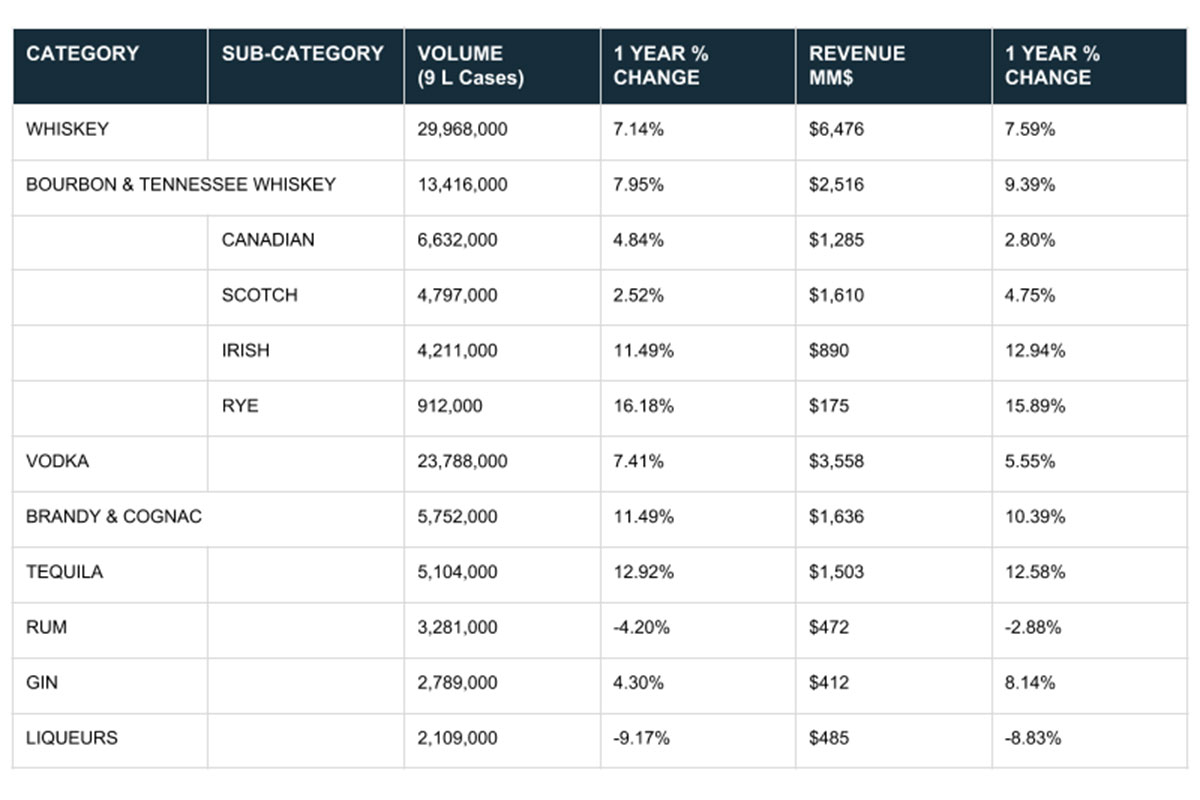

We’ll start by looking at national data for the spirit industry to get a sense of trends in the US. Distilled Spirits Council of the US (DISCUS) provides data that will show you what’s selling and where. There are also several places where you can get a state-by-state breakdown of spirits consumed by volume and revenue, but generally you have to pay for those (which is worth the investment to ensure your able to turn a profit). Below is a chart that represents consumption nationally. High-End Premium and Super Premium is typically the craft market that DISCUS tracks.

Survey Your Community

Having a national overview of spirit consumption is great, but it’s simply meant to give you an initial idea of the ratios for your spirits. Now, you need to get out into your community and start surveying people to figure out what the locals are actually drinking. This looks different depending on your distillery model, but understanding what people in your community are actually drinking will be extremely important. If you’re going to be starting a distillery bar, you really need to get out and talk to local bartenders and bar managers. If you are only planning on making bourbon and American single malt (which is a pretty common choice), then it’s probably a safe bet to make 2.79 barrels of bourbon for every barrel of single malt—at least until you find out you make a killer single malt but only average bourbon, or you find out that people in your area mainly drink single malt and not bourbon.

The next thing to look at is how spirits are produced. The easiest way to make spirits that taste great is to get the right equipment to make that type of spirit. If you’re like most distillers that are starting out, you can’t afford to have a separate still for your on-grain bourbon and your off-grain single malt, with a third (column) still for your vodka and a fourth for your gin. And there is very little chance you’ll have enough room for all of those production types. There are two common ways to solve that problem: one is to buy one of those “do everything” stills. However, they tend to be more expensive than a single-purpose still and don’t do any single task quite as well. The other option is to look for spirits that have similar production methods and only produce those. For example, if you want to produce whiskey, select on-grain or off-grain, design your products to all be made that way! Sure, your bourbon may not be made the traditional way, but that doesn’t mean it won’t still be excellent. Generally, we lump spirits into four categories; grain-based, sugar-based, vodka and flavored vodka.

Grain-Based Spirits

Grain-based spirits are all of your spirits that need to convert starch into sugar as the primary step (basically whiskey, thought a grain-based distillery can also make the inputs for a vodka or flavored vodka spirit using rice or potatoes).

Sugar-Based Spirits

Sugar-based spirits are those that already have sugar present in the fermentable material. These would primarily be brandy, fruit brandies, agave spirits, and rum. If you specialize in these, they can also be an input to a vodka or a flavored vodka distillery.

Vodka

Vodka is different despite coming from a grain or sugar-based feedstock because it needs to be distilled to such a high purity that it is difficult to use the same still for vodka to make anything else. In 2017, testing was done to all of the spirits submitted to the ADI spirit competition and 80% of the vodka submitted had chemicals in them that indicated that it had not been distilled above the 95% alcohol required to call them vodka. Therefore, if you want to make vodka, we strongly suggest buying a specialized still.

Flavored Vodka

Flavored Vodka is a category we use to refer to spirits that add flavor to neutral bases. This includes things like gins and liqueurs as well as the outrageously-flavored things like bacon flavored vodka (yum). Adding flavor requires different equipment than a traditional still whose job is to simply remove flavor. At minimum, it requires a tank where hot or cold macerations can be done all the way up to stills that put botanicals into the spirit or the vapor path during distillation.

While it certainly isn’t the wrong to produce spirits from all four of the groupings, it will likely require much more time, planning, and investment to get each spirit ready for market. Which means you may have to make other compromises later down the road.

Now that we know what spirit(s) we’re going to be selling, it’s time to sit down with your business plan and determine how much you will need to manufacture. From here on out, understand that the details of your distillery — from production methods to the production floor — will be an iterative process: you will have to make some assumptions, test them out, learn from those tests, and go back to revise your assumptions. It can be extremely helpful at this point to talk with people who have done this before, who can save you a lot of time, money, and frustration by helping you avoid some common pitfalls. We’ve found that most local distillers will happily share their story and “lessons learned” with you. Another option is to talk with a distillery consultant like the folks here at BoozeWerks. We’ve helped countless soon-to-be distillery owners get on the right path to success.